In Solidarity with the Tutuilan

Decolonise History of Art contribute to University of Cambridge Museums’ ‘Museum Remix: Unheard’ challenge

In response to the University of Cambridge Museums’ (UCM) ‘Museum Remix: Unheard’ challenge, we made a compilation of reflections on the blatant colonial perspective that governs British museums. The audio and full transcript and credits are linked to at the bottom of this post.

We purposefully exceeded the brief – to respond to one of 9 works from across their collections in 3 minutes or less – to bring attention to broader decolonial issues, notably encompassing the fight for the repatriation of the Gweagal Spears to the indigenous Gweagal people of Australia.

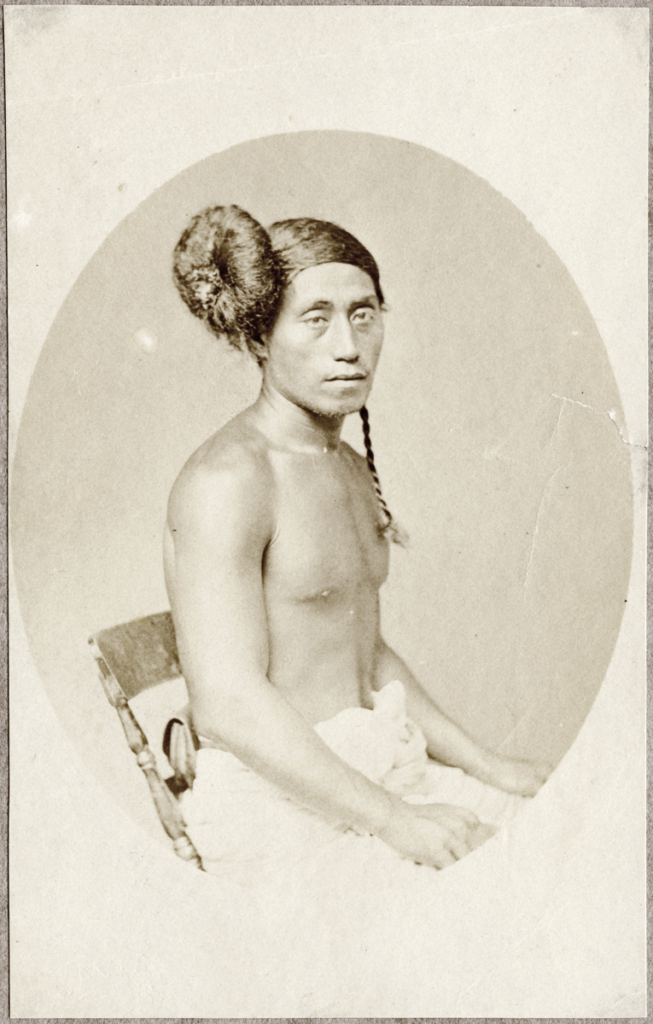

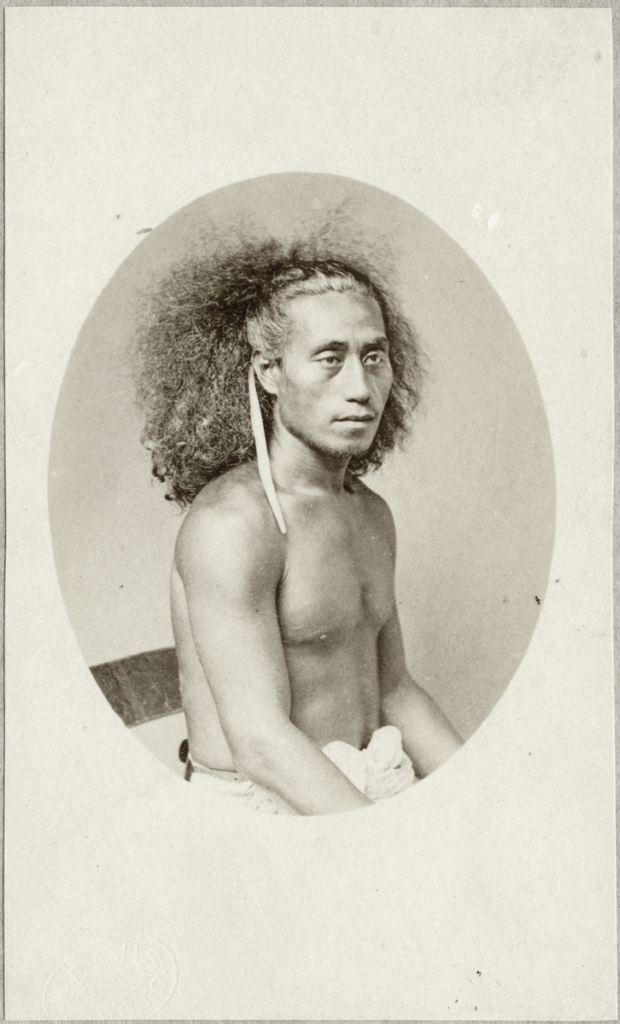

We responded to “Man from Tutuila with hair bound [and] unbound” in the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA). These photographs from colonial Samoa depict a fa’afafine person, identified by their hairstyle and pose. Fa’afafine is a Samoan term that can be translated as ‘third gender’ and, according to UCM, “expresses gender fluidity and encompasses all LGBTQ+ people.”

Through their central placement, consistent pose, expression and background in both images, the discrepancy of this Tutuilan person’s hairstyle is made the focus of these photographs. While the 3/4 profile and torso-length frame is common to western portraiture, the lack of other identifiable features gives these photographs the undeniable air of an encyclopaedic entry.

The taxonomical character of these photographs is made clearer by the subjugation of of their gender to western understanding. It is clear in the Museum: Remix brief that the MAA curators know ‘man’ is not the appropriate way to describe this person, yet the reductive label remains.

This unabashed prioritising of the western gaze is the unifying feature of these photographs and the Gweagal Spears; the refusal by the MAA to return the Spears is a clear indication of this. Rodney Kelly – activist and descendent of Cooman from whom the Spears were stolen in 1770 – has stated that having the Spears returned to Australia is essential to the survival of Indigenous culture, both for the Gweagal people themselves, and for broader awareness in Australia. In prioritizing western ownership the UCM continue to stand with the colonisers John Davis (photographer) and Anatole von Hugel (collector).

Another focus of our response is UCM’s unwillingness to make lasting change in their pursuit of decolonisation. The very premise of Museum Remix allows UCM to perform a willingness to diversify the points of view it validates, without having to implement structural change to the way their insitutions operate. Our critique thus aligns with the demands of the recent open letter to UCM by Decolonise History of Art and Decolonise Archaeology, which asserts the need for:

- “Better representation and support of BIPOC employees and students;

- A UCM-wide research initiative to reveal the colonial factors behind UCM’s collections;

- Changes to the display of [UCM] collections;

- Re-evaluation of [UCM’s] approach to repatriation”

Central to the issue of structural change is that of expertise. In contrasting personal poetic and descriptive responses to Davis’ photographs with the activist expertise of Rodney Kelly, we have sought to challenge both the notion of an ‘expert’ and the premise of the exercise.

Often overlooked is the practical expertise of activists and Indigenous people themselves, such as Kelly, who has been advocating for the repatriation of the Gweagal Spears for years. The Museum Remix is rather conspicuously pitched only at the general public, and makes no mention of previous or ongoing colonial disputes it is involved in.

To be clear, opening up the collections to the interpretations of the general public is an exciting step towards anti-elitism in museums. However, when not combined with the enfranchisement of BIPOC experts that have been working towards making these stories known for decades, it becomes a poor imitation of change.

Editing by Tae Ateh; Voiceover by Izzy Collie-Cousins; Original words by Izzy Collie-Cousins & Tae Ateh; with words by Rodney Kelly, Beverly Carpenter of Oblique Arts, and protesters advocating for the repatriation of the Gweagal Spears.

Band of Protesters: Rodney Kelly (digeridoo), Banjo Nick Rambles (voice, banjo and percussion), Gene Thunderbolt McCarthy (electric guitar). Tae Ateh (ranting and percussion)

TRANSCRIPT:

PROTESTORS: (chanting) Thieves! Liars! Thieves! Liars!

Thieves! Liars!

(continuous banjo & digeridoo music)

Trinity!

VOICEOVER: Somewhere on a shelf a person sits amongst

the remnants of lives gone by, oceans away.

This trophy-case is one in a forest of many

polished, categorised silos, each made unique

by the particular uniformity of its fragments.

While eyes darting through the silence might

miss those of this Tutuilan, a moment’s

contemplation reveals our ghostly reflection

next to theirs. Their physicality is more certain

than our glass-bound reflection.

PROTESTORS: (singing during VOICEOVER)

Two hundred and forty-eight years!

Give back the Gweagal Spears!

Two hundred and forty-eight years!

Give back the Gweagal Spears!

(music & chanting stops)

BEVERLEY CARPENTER: How does it make you feel when you see this

whole museum?

RODNEY KELLY: Ah, you know, it makes me a bit angry –

because my culture’s just confined to these

little parts here from my area, and we’ve got

other different tribal stuff here from other

tribes. You look around the room and there’s

so much stuff from everywhere, and nobody’ll

ever come here to learn the true history about

these artefacts. They're just going to look at

them as spears, as wooden objects. Back home,

if we had them in our museum, I guarantee

every time somebody views them spears

they're gonna know what happened that day,

who made ‘em, and they’re actually going to

hear the story from the descendants of the

people who were there that day. So that’s

gonna be an amazing history lesson for the

many people who are gonna walk into our

museum back home and view these items.

VOICEOVER: (overlapping with RODNEY KELLY)

Without me, I’m not here, you are

Dead eyes, white lies

Don’t gaze at me

I’m not a man, I’m not an exhibit

misgendered, misplaced, mistraced

You stole me and locked me away

You cut me off and cut pieces off me and you

stand here and look at me

But I am not an object

I am not a man, I am not yours

This is not human or mineral or vegetable

I am not something you can contain or

understand without my whole presence

Without me, I’m not here, you are

Dead eyes, white lies

Don’t gaze at me

I’m not a man, I’m not an exhibit

misgendered, misplaced, mistraced

You stole me and locked me away

You cut me off and cut pieces off me and you

stand here and look at me

I’m not an object

I am not a man I am not yours

I am not, I’m not, and I’m not an object, and I’m -

VOICEOVER: What I see here is hair bound and unbound.

The fetishization of a single, defining feature

of an entire person, because the western

explorer found it strange. What we don’t see is

attention to detail in accurately representing

this person's gender. We know that they were

likely fa’afafine, and yet we still describe them -

RODNEY KELLY: (overlapping with VOICEOVER)

[…] get what they deserve because they’re

really significant items and they’re one of a

kind. They're so important to our culture and

to the survival of our culture. In a lot of areas

it is under threat. [In] some places we’re

slowly starting to regain our language and our

toolmaking processes. But something like

these spears, having them back home, they’re

gonna kickstart so much more for the public

of Australia. Everybody knows that Australia

has a lot of, the government’s got a lot of racist

policies.

VOICEOVER: (overlapping with RODNEY KELLY)

Instead, they gaze through us, as they will

have gazed through visitors many times

before. They have transgressed borders and

timelines to look at us here, the English

Channel lapping at the confines of the

photograph; the gentle slope of Samoan sand

meeting the unending expanse of ocean is a

distant and hazy memory. Ever within John

Davis’ studio, solely for the western beholder,

characterised by othered attributes that would

be familiar at home, but, here, must be singled

out in ways we can understand: they sit, and

they stare.

PROTESTERS: (singing during VOICEOVER)

Two hundred and forty-eight years!

Give back the Gweagal Spears!

Two hundred and forty-eight years,

Give back the Gweagal Spears!